Can You Be Honest With Yourself?

Have you ever been long excited about a trip/vacation only to find yourself disappointed as soon as it begins? Did you brush off the disappointment with an excuse like, “I’m just tired from the travel”? Well, whatever the reason, that disappointment was trying to tell you something.

Most of us have been trained since childhood to distrust our emotions so we become unable to trust ourselves, and when we should be walking away from a situation that will end up hurting us in some way, we pull out a chair and order a drink.

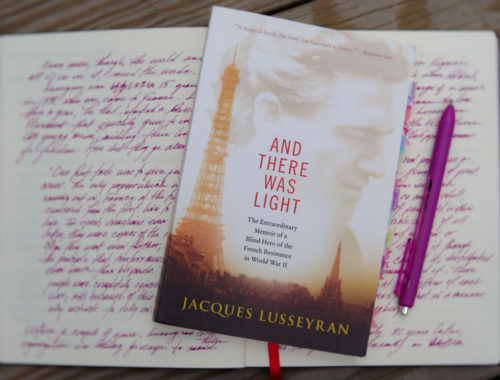

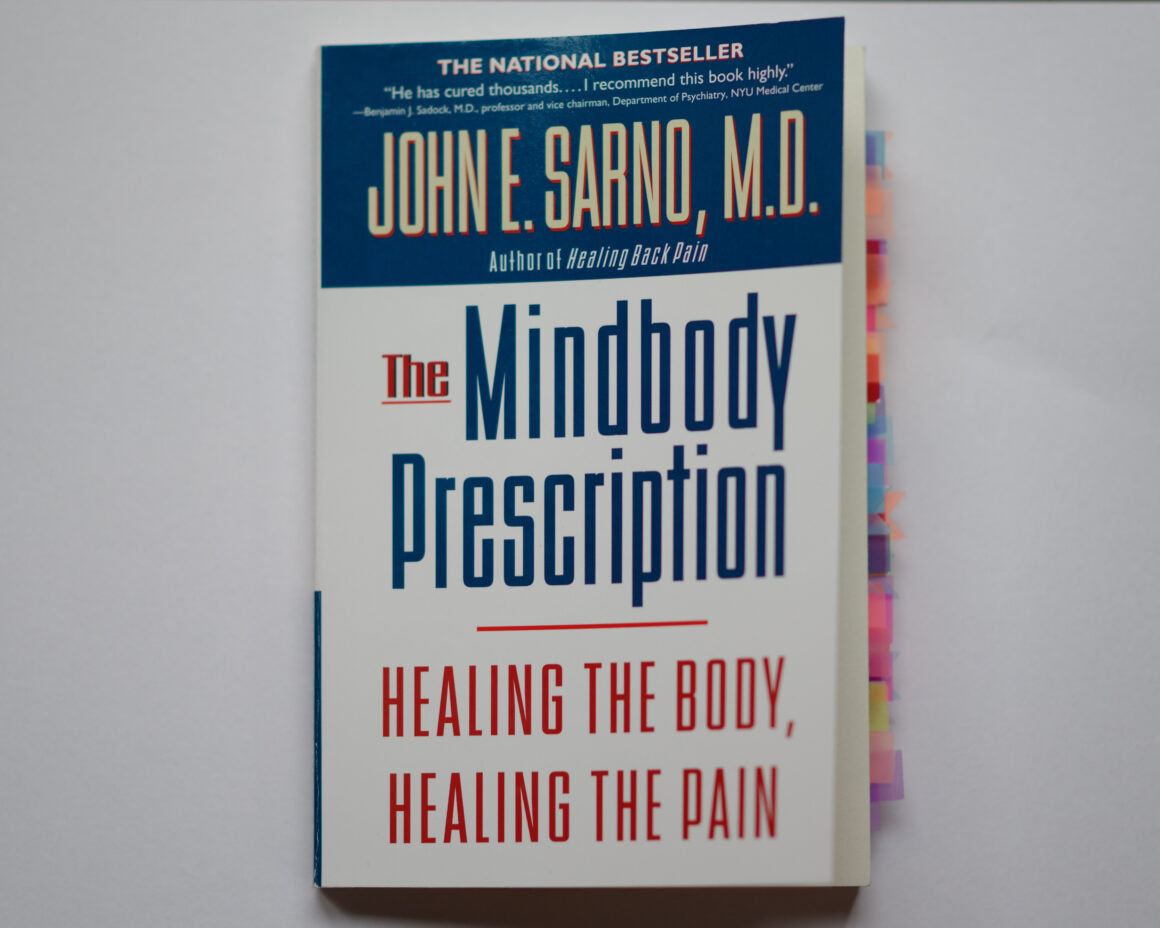

Nothing of the sort happened to me at my son’s wedding on June 1st. I was happy to be there and was so busy enjoying each moment that the entire day flew by in what seemed like 60 minutes. The rehearsal the evening before was just as good, if not better. It was then that I finally got to meet some of Luke’s Florida friends: Patrick, Reid, and Jed, and our conversations led to one of them telling me about a book he had read years ago and found quite helpful. I took note of the author and looked him up the day after the wedding, adding the book to a list, but in less than a week, I had a copy in my hand, courtesy of Reid.

I’m still reading it (along with another dozen books) and finding it fascinating, as The Mindbody Prescription validates Alice Miller’s theories but comes at them from the opposite direction. Physician John Sarno discovered that physical health is commonly sabotaged by repressed emotions; psychologist Alice Miller, on the other hand, discovered that repressed emotions often sabotage physical health.

Only 46 pages in, the book is already studded with about 50 page flags. Here is one marked passage, an iteration of Sarno’s thesis, confirmed by decades of clinical experience and thousands of patients:

Conflicts rage constantly in the unconscious, born of the various elements that represent the mosaic of the human psyche. These conflicts result in the development of emotions that cannot be tolerated and, therefore, must be repressed. Because these undesirable feelings appear to strive for recognition, the mind must do something to prevent them from coming to consciousness. Hence, the mindbody symptom. This book explores the nature and content of these undesirable feelings and explains why the mind chooses to mask emotional turmoil with physical pain.

Sarno explains that the word that encompasses all emotionally induced physical disorders is psychogenic, and he lists a number of them, including: most low back and leg pain; most neck, shoulder, and arm pain; fibromyalgia; carpal tunnel syndrome; many cases of Epstein-Barr syndrome; gastrointestinal disorders; disorders of the circulatory system; skin disorders; disorders of the immune system; and genitourinary disorders. Further, he states that emotions may play a role in autoimmune disorders, cancer, and cardiovascular disorders.

Sarno purposefully does not use the word psychosomatic because it is just one manifestation of psychogenic disorders and is too often taken to mean “imaginary,” which is absolutely not the case. The conditions are very real, but they are caused by the brain trying to shelter itself from painful recognition. What’s more, mental/emotional issues such as anxiety, depression, and obsessive-complusive disorder are the results of repressed emotions, usually rage, and Sarno is not the only professional to recognize this. I’ve come across the same assertions in books by Alice Miller, Joost Meerloo, and Ashley Montagu and in social media posts from numerous doctors and therapists.

But where does this rage come from? Sarno points to three potential sources: “that which may have been generated in infancy and childhood and never dissipated”; “that which results from self-imposed pressure, as in driven, perfectionist, or goodist [his term for those driven to be and do good] people”; and “that which is a reaction to the real pressures of life.” What he does not seem to understand (at least, thus far) is that being driven to succeed, to be perfect, to never fail, to be someone others admire is a result of childhood experiences that communicate the notion that love needs to be earned. (I’ve written about this in previous posts).

Sarno’s conclusion about rage being at the heart of most of this stuff is the interesting one, but thus far, he hasn’t said much about conflict or guilt, which are closely linked with the rage. So here’s some of what Joost Meerloo had to say in The Rape of the Mind:

Deep within all of us lie hidden feelings of guilt, unconscious guilt, which can be brought to the surface under extreme stress. The strategy of arousing guilt is the mother’s oldest tool for gaining dominance over her children’s souls. Her warning and accusing finger or her threatening eyes give her a magic power over them and help to create deep-seated guilt feelings which may continue all through their adult lives. When we are children, we depend on our parents and resent them for just this reason. We may harbor hidden destructive wishes against those closest to us, and feelings of guilt about these wishes. There is no question that most men have a profound loyalty to their families, but the primitive in him hates those he loves, and this hatred makes him feel guilty. Buried deep in his unconscious is the knowledge that in his hostile fantasies he has felt himself capable of committing many crimes.

Make no mistake; these are not new ideas. The Rape of the Mind was published in 1956; The Mindbody Prescription was published in 1998, and Miller’s first book, The Drama of the Gifted Child, in 1979. So why isn’t the mainstream medical community acknowledging the roles emotions and the brain play in many physical conditions? Well, why would they? Not only are most doctors repressing emotions like the rest of us, they, too, have to support their families. According to my browser’s summarizer, “Chronic pain in the US costs up to $635 billion annually, which is more than the yearly costs for cancer, heart disease, and diabetes.” We won’t bother to investigate how much dough complaints like anxiety and depression generate for the medical-industrial complex, but there’s little doubt that it rings up in the billions.

Since this post is getting long and your time is valuable, I’ll end by sharing the most powerful part of The Mindbody Prescription that I’ve encountered so far: the story of one of the author’s patients. He gives her the name of “Helen” and explains that he had successfully treated her for back pain by teaching her to recognize that her pain was being generated by her brain. All was well for a few months, but then, at the age of 47, Helen remembered having been sexually abused by her father. Sarno does not share the circumstances surrounding the surfacing of this repressed memory, but he explains that Helen joined a support group for adult women survivors of incest. The day of the first meeting, her back pain returned. She writes:

I went to the meeting, met the six other women, trying to keep kind of under control and not be totally emotional and miserable with people I had barely met. I wanted to see if this kind of group was really right for me. I found myself, in spite of trying to keep some distance, very much overwhelmed—by the amount of pain and havoc wrought in these women’s lives, as well as my own, by the abuse.

Over the next two days, Helen’s back pain increased to the point at which she could not get out of bed. She told her husband that she understood where the pain was coming from, and asked why it wasn’t going away. He replied, “You’re talking about forty years of repressed anger.” This, in Helen’s own words, is what followed:

And, then, in an instant, I started to cry. Not little tears, not sad, quiet oh-my-back-hurts-so-much tears, but the deepest, hardest tears I’ve ever cried. Out of control tears, anger, rage, desperate tears. And I heard myself saying things like, Please take care of me, I don’t ever want to have to come out from under the covers, I’m so afraid, please take care of me, don’t hurt me, I want to cut my wrists, please let me die, I have to run away, I feel sick—and on and on, I couldn’t stop and R——, bless him, just held me. And as I cried, and as I voiced these feelings, it was, literally, as if there was a channel, a pipeline, from my back and out through my eyes. I FELT the pain almost pour out as I cried. It was weird and strange and transfixing. I knew—really knew—that what I was feeling at that moment was what I felt as a child, when no one would or could take care of me, the scaredness, the grief, the loneliness, the shame, the horror. As I cried, I was that child again and I recognized the feelings I have felt all my life which I thought were crazy or at the very best, bizarre. Maybe I removed myself from my body and never even allowed myself to feel when I was young. But the feelings were there and they poured over me and out of me.

I hope you take a moment now and try and imagine what this woman went through as a child. Have you ever been objectified by someone you thought cared about you? If so, I pray that it was never in such a heinous, reprehensible way when you had no ability to defend yourself. Whatever the circumstances, I’m sure it hurts—as it should.